I’m going to tell you a little bit about a package I’ve just put together which lets you exclude certain files from the ASP.Net change notifier (the thing which restarts your IIS app pool whenever you change certain files). On the way, we’re going to dig into some internal framework code, and I’m going to horrify you with some code that should definitely never get run in production! Let’s start with the inspiration for this work.

A Bad Dev Experience

The dev experience on one of our legacy projects had been annoying me for a while: whenever I triggered a Gulp build, my IIS app pool would restart. That sometimes had (annoying) flow-on effects, and we ended up with various work-arounds depending on what we were doing. It was never a priority to fix, because Gulp builds only happened on dev and CI machines, never in deployed environments – but one week it really got in the way of some work I was doing, so I decided to get to the bottom of the problem.

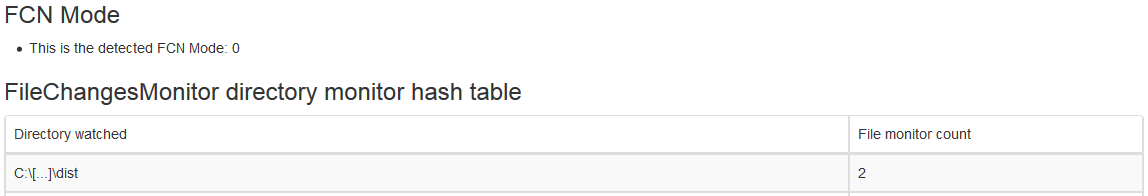

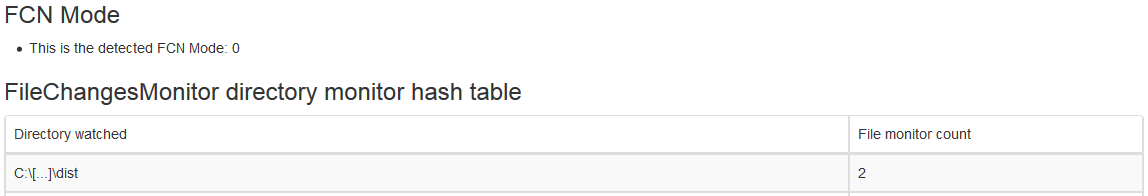

You may know that ASP.Net will restart your application whenever there are changes to your web.config or any files in your /bin folder. What you might not know (I didn’t) is that it can also monitor various other files and folders in your application, and what it monitors doesn’t seem to be well-documented. Our Gulp build dumps the output into a /dist folder, and ASP.Net was restarting our app every time any file in that folder changed. After a little Googling, I discovered a StackOverflow answer which gave a slightly-hacky way to disable the ASP.Net file monitoring, which I did – and it worked. No more app restarts!

Not So Fast…

After a few hours of front-end work, I needed to make some back-end changes. I finished wiring up my API endpoints, ran the project, and expected success! No luck. After some more tinkering with the front-end, I suspected my C# code – but after some checking, it was definitely correct: I had the unit tests to prove it. Eventually I fired up the debugger, and found my problem: the debugger was reporting that the running code didn’t match my file. Disabling file change notifications had also disabled notifications on the /bin folder, so my rebuilt DLL files weren’t being loaded. I wasn’t prepared to accept rebuilds not triggering reloads, so I needed to revisit my solution.

Before I went too far, I wanted to be really sure that I was looking at the right problem. It turns out someone going by the name Shazwazza has already done the hard work to build a list of files and folders ASP.Net is helpfully monitoring for changes, and yes – there is my Gulp output folder.

What I really want is to be able to preserve all of the existing functionality – but skip monitoring for certain paths. I investigated a few different switches and options, but none of them gave me exactly what I wanted. I was going to have to get my hands dirty.

Diving Into Framework Code

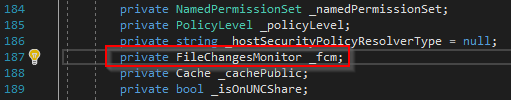

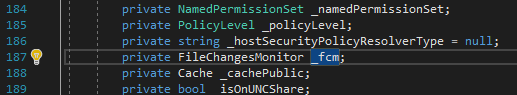

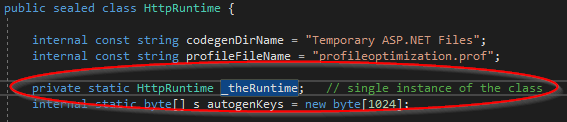

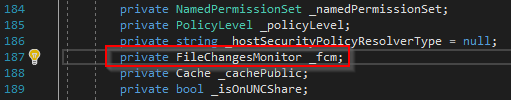

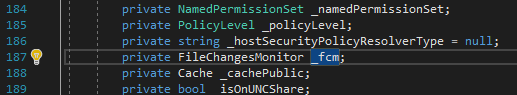

Having read Shazwazza’s code, I had already learned that the file monitor is stored on the HttpRuntime singleton, so I started my investigation there. I was hoping it just stored a reference to an interface, so I could just replace it with my own wrapper over the base implementation.

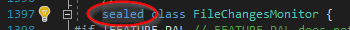

Well, no interface – but I suppose I can just subclass FileChangesMonitor and use reflection to swap the base implementation out for my own.

Oh. It’s a sealed class – so I can’t even subclass it. It was about this point that I stopped trying to solve the problem on work time: this had become a personal mission, and I wasn’t going to give up until I’d made this thing behave the way I wanted to.

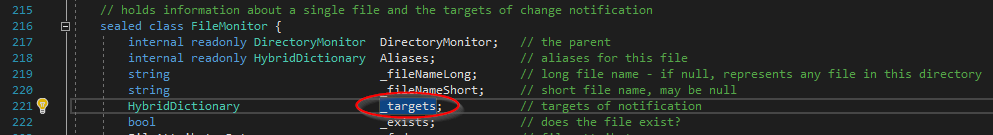

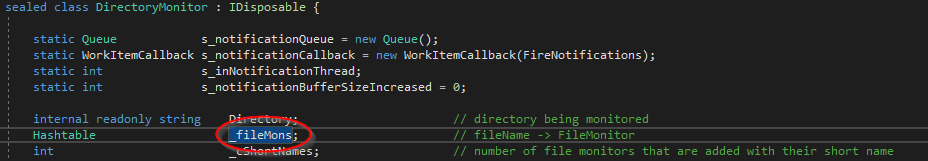

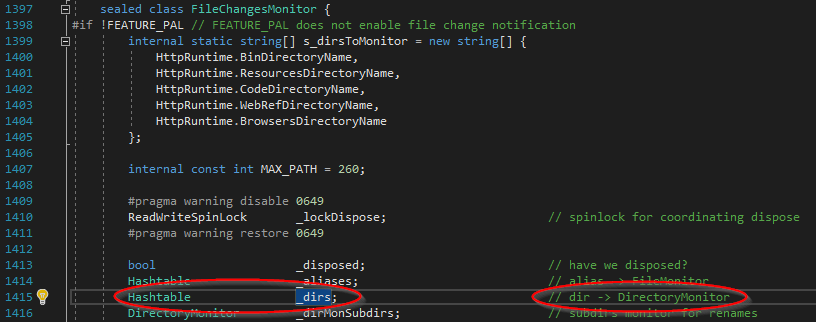

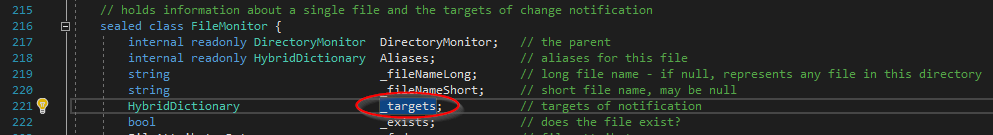

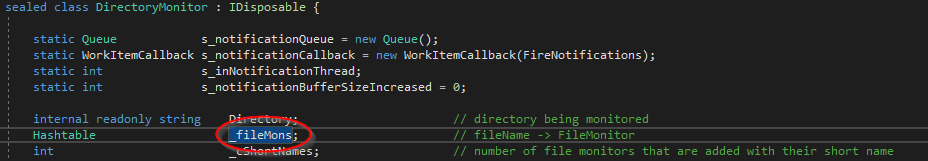

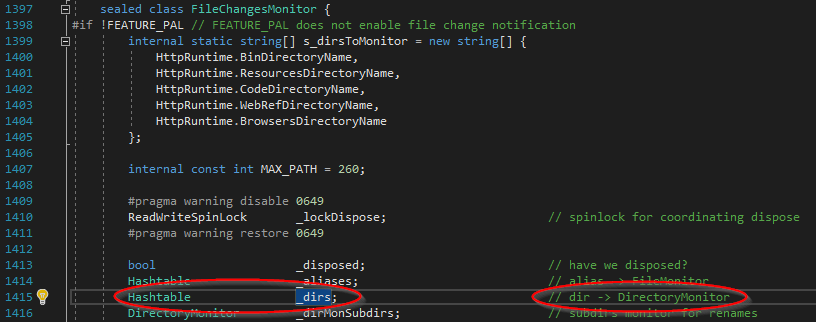

First, I needed to get a solid understanding of how the FileChangesMonitor class worked. After a lot of reading, it boils down to this: other classes ask the FileChangesMonitor to monitor a particular path, and it maintains a hash of paths to DirectoryMonitor instances which it creates. In turn, DirectoryMonitor has a hash of filenames to FileMonitor objects it has created, and FileMonitor has a HybridDictionary which stores callbacks. FileChangesMonitor, DirectoryMonitor, and FileMonitor are all sealed classes, so it looks like I’m out of luck – but I refused to be beaten!

The core classes I’m dealing with are all sealed, so there’s definitely no option to change behaviour there – but at each step of the object hierarchy, a parent object is storing instances of these sealed classes in plain old collection types: Hashtables and HybridDictionaries. Those classes aren’t sealed, so that’s going to have to be the seam where I stick my metaphorical crowbar.

A Word of Warning

If the idea of messing with private-member Hashtables makes you nervous, good. I’m about to go messing with the internals of framework classes in a very unsupported, highly-fragile way. This is not production-quality code. This is nasty, hacky code which is probably going to break in the future. If you ever use this code, or this extension technique, please do it in a way which will never, ever, ever run on a production machine.

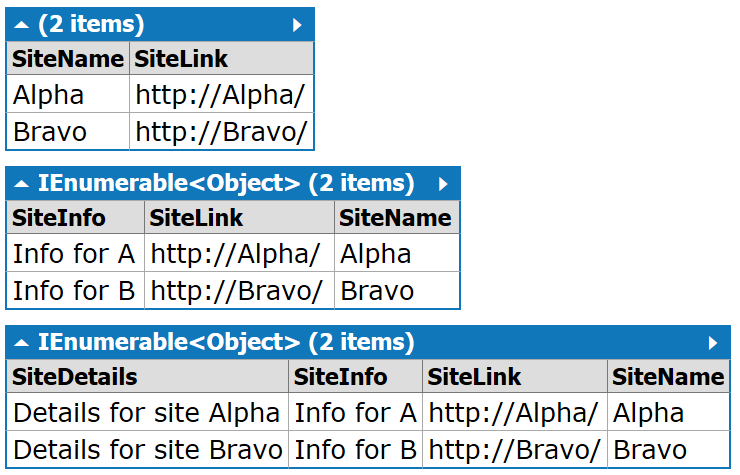

If you love the idea of #antiproduction code, you’ll probably enjoy my Object.Extend(…) implementation and my .ToRandomCollectionType<>() LINQ extension.

I’m trying to fix the dev experience here, and so I decided to accept the hacky nature – but I have put plenty of guards around it to keep it clear of our production machines. I’ve even made sure it stays clear of our test environments. It’s a local-dev-environment only thing!

A Note on Reflection

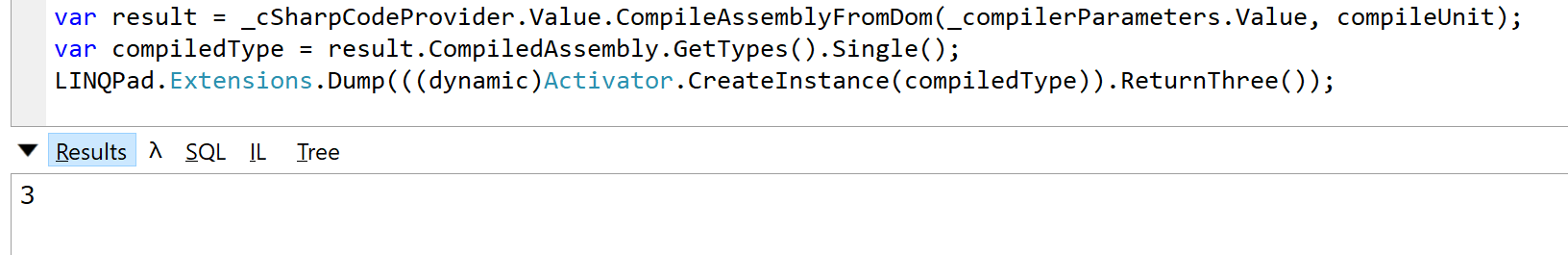

If you’re familiar with the .Net reflection API, you’ll know it can be a little clunky. I’m using the following extension methods to make my code look a little cleaner.

public static class ReflectionHelpers

{

public static FieldInfo Field(this Type type, string name) => type.GetField(name, BindingFlags.NonPublic | BindingFlags.Instance);

public static FieldInfo Field<T>(string name) => typeof(T).GetField(name, BindingFlags.NonPublic | BindingFlags.Instance);

public static FieldInfo StaticField<T>(string name) => typeof(T).GetField(name, BindingFlags.NonPublic | BindingFlags.Static);

public static ConstructorInfo Constructor(this Type type, params Type[] parameters)

=> type.GetConstructor(BindingFlags.NonPublic | BindingFlags.Instance, null, parameters, null);

public static MethodInfo StaticMethod(this Type type, string name, params Type[] parameters)

=> type.GetMethod(name, BindingFlags.Static | BindingFlags.NonPublic, null, parameters, null);

public static Type WebType(string name) => typeof(HttpRuntime).Assembly.GetType(name);

public static Object Make(this ConstructorInfo constructor, params Object[] parameters) => constructor.Invoke(parameters);

public static Object Call(this MethodInfo method, params Object[] parameters) => method.Invoke(null, parameters);

}

How I Hooked (Hacked) FileChangesMonitor

What I really want to do is to prevent FileMonitor from setting up file watches for specific paths, and my only extension point is the HybridDictionary of watches. When FileMonitor is asked to set up a watch, it checks its dictionary to see if there’s already one there for that specific callback. If it doesn’t already have one, it sets one up. So what I need is a HybridDictionary which always has an entry for any given callback!

Sadly, HybridDictionary doesn’t declare its methods as virtual, so we can’t just go overriding them. Fortunately, it does just use a Hashtable under the covers – and we can use some reflection trickery in the constructor to replace the Hashtable it creates with one of our own design!

/// <summary>

/// Intercepting hybrid dictionary. It always responds to any key request with an actual value

/// - if it didn't exist, it creates it using a FileMonitor factory.

/// HybridDictionary always uses a hashtable if one has been constructed, so we just rely on InterceptingHashTable.

/// This relies on an implementation detail of HybridDictionary but we're way past worrying about that kind of thing at this stage.

/// </summary>

public class MonitorInterceptingHybridDictionary : HybridDictionary

{

static Type EventHandlerType = WebType("System.Web.FileChangeEventHandler");

static ConstructorInfo FileMonitorConstructor = WebType("System.Web.FileMonitorTarget").Constructor(EventHandlerType, typeof(string));

public MonitorInterceptingHybridDictionary()

{

var fakeTable = new InterceptingHashTable(o =>

{

try

{

return FileMonitorConstructor.Make(null, "test");

}

catch (Exception ex)

{

Log.Error(ex, "Unable to create a file monitor target pointing at {Target}", o);

return null;

}

});

Field<HybridDictionary>("hashtable").SetValue(this, fakeTable);

}

}

Our new HybridDictionary is using another new class I’m going to re-use shortly – the InterceptingHashTable. Here, we finally catch a break: Hashtable declares a lot of its methods as virtual, so we can override functionality. What we’re going to do here is to create a new subtype of Hashtable which always has the key you’re looking for, even if it hasn’t been added. We pass a factory function in to the constructor, so whenever something asks for the value for a given key, we can construct it on the fly if it hasn’t already been added.

/// <summary>

/// Intercepting hash table. It always responds to any key request with an actual value

/// - if it didn't exist, it creates it with the provided factory.

/// This currently only implements this[key] because that's all the file monitor stuff uses.

/// To be generally useful it should override more methods.

/// </summary>

public class InterceptingHashTable : Hashtable

{

private readonly Func<object, object> _factory;

public InterceptingHashTable(Func<object, object> factory)

{

_factory = factory;

}

public override Object this[Object key]

{

get

{

var maybe = base[key];

if (maybe == null)

maybe = CreateMonitor(key);

return maybe;

}

}

public Object CreateMonitor(Object key)

{

return _factory(key);

}

}

If you take a look back at the MonitorInterceptingHybridDictionary code above, you’ll see that it’s going to pretend it’s already got a FileMonitorTarget anytime something looks – and that means the calling FileMonitor will think it’s already got a watch on the file, and skip creating it. Bingo! The next step is to replace the HybridDictionary on FileMonitor with an instance of our new class.

Of course, it’s a private member, and we’ve currently got no way to hook the creation of FileMonitor instances. What does create FileMonitor instances? The DirectoryMonitor class – and fortunately for us, it keeps a Hashtable of all of the FileMonitors it’s created. That means we can swap out the Hashtable for another of our InterceptingHashTables, and every time the DirectoryMonitor looks to see if it already has a matching FileMonitor, we create it if it doesn’t already exist.

// Create a dodgy hashtable which never has a blank entry - it always responds with a value, and uses the factory to build hacked FileMonitors.

var fakeFiles = new InterceptingHashTable(f =>

{

try

{

// Build a FileMonitor.

var path = Path.Combine(o as string, f as string);

var ffdParams = new object[] {path, null};

ffd.Invoke(null, ffdParams);

var ffdData = ffdParams[1];

object mon;

if (ffdData != null)

{

var fLong = ffdData.GetType().Field("_fileNameLong").GetValue(ffdData);

var fShort = ffdData.GetType().Field("_fileNameShort").GetValue(ffdData);

var fad = ffdData.GetType().Field("_fileAttributesData").GetValue(ffdData);

var dacl = secMethod.Call(path);

mon = fileMonConstructor.Make(dirMon, fLong, fShort, true, fad, dacl);

}

else

{

// The file doesn't exist. This preserves the behaviour of the framework code.

mon = fileMonConstructor.Make(dirMon, f as string, null, false, null, null);

}

// Break the FileMonitor by replacing its HybridDictionary with one which pretends it always has a value for any key.

// When the FileMonitor sees it already has this key, it doesn't bother setting up a new file watch - bingo!

var fakeHybridDictionary = new MonitorInterceptingHybridDictionary();

mon.GetType().Field("_targets").SetValue(mon, fakeHybridDictionary);

// Take this warning away later

Log.Debug("Provided fake monitoring target for {Filepath}", path);

return mon;

}

catch (Exception ex)

{

Log.Error(ex, "Unable to create a file monitor for {Filepath}", f as string);

return null;

}

});

Now, we’re faced with another problem: we have no control over the creation of DirectoryMonitor instances, but we need to replace the private Hashtable it keeps with the fake one we’ve just made.

Luckily for us, the FileChangesMonitor class keeps a Hashtable of DirectoryMonitors!

You might be able to guess where this is going: we need another fake Hashtable which always creates DirectoryMonitor objects on the fly. Stay with me here, we’re approaching the end of this thread we’ve been pulling on.

// This is a factory which produces hacked DirectoryMonitors. DirectoryMonitor is also sealed, so we can't just subclass that, either.

Func<object, object> factory = o => {

try

{

if (!(o as string).Contains(@"\EDS\dist"))

{

Log.Debug("Allowing file change monitoring for {Filepath}", o as string);

return null;

}

var dirMon = dirMonCon.Make(o as string, false, (uint) (0x1 | 0x2 | 0x40 | 0x8 | 0x10 | 0x100), fcnMode);

// Create a dodgy hashtable which never has a blank entry - it always responds with a value,

// and uses the factory to build hacked FileMonitors.

// ... the previous code block goes here ...

// Swap out the hashtable of file monitors with the one which lets us always create them ourselves.

dirMon.GetType().Field("_fileMons").SetValue(dirMon, fakeFiles);

return dirMon;

}

catch (Exception ex)

{

Log.Error(ex, "Unable to create a directory monitor for {Filepath}", o);

return null;

}

};

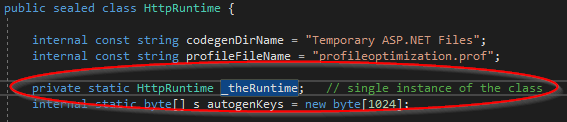

Finally, the HttpRuntime class holds a reference to a single copy of FileChangesMonitor, and HttpRuntime itself is a singleton!

With a little more reflection, we can therefore swap out the Hashtable in FileChangesMonitor with our hacked Hashtable of DirectoryMonitors, and now we have control of all the instantiation of DirectoryMonitors and FileMonitors, and we can intercept any filenames we don’t want tracked and provide dummy FileMonitorTarget responses to prevent the watches from being set up.

/*

* I am so, so sorry if you ever have to maintain this.

* ASP.Net monitors a pile of folders for changes, and restarts the app pool when anything changes.

* Gulp often triggers this - restarting the app pool unnecessarily, annoying developers. Annoyed developers write code like this.

*/

var httpRuntime = StaticField<HttpRuntime>("_theRuntime").GetValue(null); // Dig out the singleton

// Grab the FileChangesMonitor. It's a sealed class, so we can't just replace it with our own subclass.

var fcm = Field<HttpRuntime>("_fcm").GetValue(httpRuntime);

// Grab a bunch of internal types, methods, and constructors which we're not meant to have access to.

var dirMonType = fcm.GetType().Field("_dirMonSubdirs").FieldType;

var dirMonCon = dirMonType.Constructor(typeof(string), typeof(bool), typeof(uint), typeof(int));

var fileMonType = dirMonType.Field("_anyFileMon").FieldType;

var fadType = fileMonType.Field("_fad").FieldType;

var fileMonConstructor = fileMonType.Constructor(dirMonType, typeof(string), typeof(string), typeof(bool), fadType, typeof(byte[]));

var ffdType = WebType("System.Web.Util.FindFileData");

var ffd = ffdType.StaticMethod("FindFile", typeof(string), ffdType.MakeByRefType());

var secMethod = WebType("System.Web.FileSecurity").StaticMethod("GetDacl", typeof(string));

// ... insert all the above code to create the factory ...

// Swap out the hashtable of directory monitors with the one which lets us always create them ourselves.

var table = new InterceptingHashTable(factory);

fcm.GetType().Field("_dirs").SetValue(fcm, table);

So what’s the up-shot of all of this? Well, firstly, I’ve written some of the nastiest, hackiest code of my career. Secondly, I’ve wrapped it all up into a nuget package so you can easily run this nasty, hacky code (it’s not up quite yet – I’ll share another post when it’s ready to go). And thirdly, I need to warn you again: Do not put this near production! I don’t care how you accomplish it, but please put plenty of gates around the entry point to make sure you don’t trigger this thing in a deployed environment. It really is a dev-only device.

Surely There’s a Better Way?

There is absolutely a better way. I encourage you to find other ways to avoid dev changes constantly churning your app pool. I strongly suspect our problem was serving our Gulp build output via a secondary bundling step: the Asp.Net bundler seems to be one of the things which might register files with the FileChangesMonitor. For various reasons (mostly, that the project was a big, complex, legacy project which is hard to test thoroughly), I strongly preferred dev-only changes to making production-affecting changes. And so here we are.

If you can find a way to avoid using this technique, I strongly recommend you do.